Disparities in Vocational Higher Secondary Education in Kerala

Vocational Higher Secondary Education (VHSE) is a specialized stream of education designed to equip students with practical skills and technical knowledge alongside their academic studies. It aims to prepare students for employment or higher education in vocational fields.

VHSE courses cover a wide range of disciplines, including agriculture, engineering, health sciences, commerce, and IT. Some popular courses include Junior Software Developer, Electrician Domestic Solutions, Agriculture Extension Service Provider, and Beauty Therapist. These courses integrate theoretical learning with hands-on training, ensuring students gain industry-relevant expertise.

In Kerala, the VHSE system is managed by the Directorate of General Education, Government of Kerala, and admissions are conducted through a centralized allotment process. Schools offering VHSE programs are spread across Kerala, providing students with access to quality vocational education. For more details, you can visit the official VHSE Kerala website.

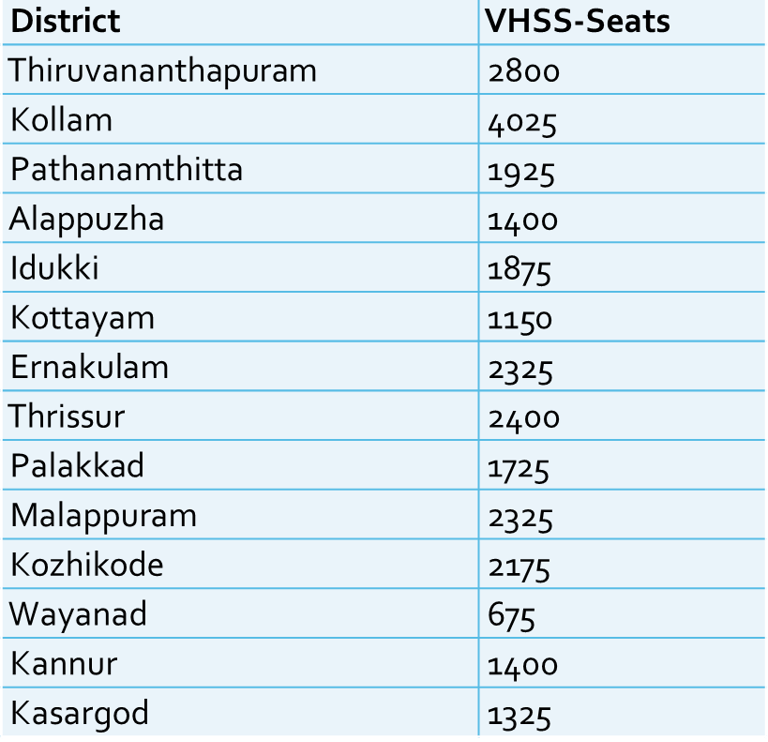

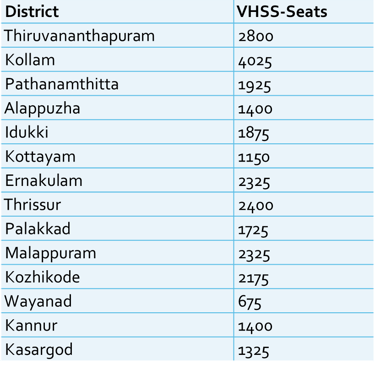

Of the total 27,525 seats available in VHSE courses across Kerala, a majority—15,500 seats—are allocated to the southern districts from Thiruvananthapuram to Ernakulam which amounts to about 56.3%. In contrast, the northern districts from Trissur to Kasaragod have only 12,025 seats, reflecting a significant difference in distribution. This has to be compared with the number of students passing class ten to understand the disparity between North and South regions. Of the students who passed class 10 examination this year (March 2025), 63% belong to the Northern region which is in clear contrast when it comes to opportunities.

This imbalance suggests that vocational education opportunities are more concentrated in the southern region in Kerala. Ideally, vocational education opportunities should align with population distribution to ensure accessibility for students across the state. To bring about solution, the people of Malabar region must interact with the administration in Trivandrum.

Abdul Jaleel P P

Member, Executive Committee

Malabar Education Movement

Reference:

Understanding Regional Disparities in Higher Education Access: A Call to Action

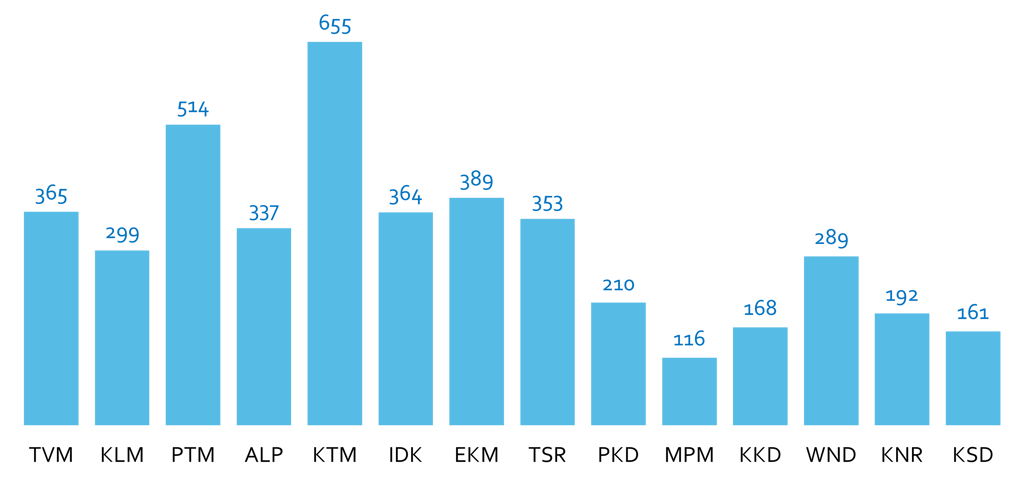

Access to higher education remains a crucial indicator of social progress and equity, especially in a diverse and populous country like India. A recent dataset released by Malabar Education Movement depicting the number of students (per 1,000) who can gain admission to undergraduate courses in government/aided private management institutions after secondary school reveals stark regional disparities across districts in Kerala.

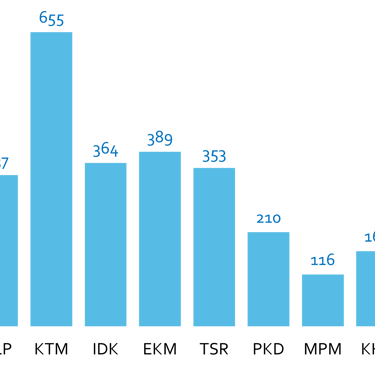

The bar graph showcases how student progression into higher education varies dramatically from one district to another. At the forefront is Kottayam, with an impressive 655 out of 1,000 students having seats available in the government/aided private management undergraduate programs. Similarly, Pathanamthitta (514) and Ernakulam (389) demonstrate relatively strong opportunities in higher education. These figures indicate a well-functioning ecosystem of secondary education, and public access to higher education in Kerala’s southern and central districts.

In stark contrast, the Malabar region, comprising districts in northern Kerala, tells a different story. Malappuram (116) records the lowest higher education opportunity in the arts and science colleges, followed by Kasaragod (161), Kannur (192), and Kozhikode (168). Despite having dense populations and a large number of secondary school graduates, these districts show significantly lower transition rates to higher education in the government/aided private management sector. This disparity underscores the presence of deeper systemic issues—such as lack of colleges and courses, socio-economic challenges, inadequate support structures, and infrastructural deficits in higher education accessibility.

These insights validate the foundational premise of the Malabar Education Movement. MEM was established to address exactly such inequities—particularly in northern Kerala—through targeted interventions, research, and advocacy. The data illustrates the pressing need for MEM’s program: sensitizing the authorities the requirement of more colleges and courses in the region.

To support its data-informed strategy, MEM has established the Centre for Educational Data Analysis and Research (CEDAR). This research hub will serve as a backbone for evidence-based decision-making, enabling the organization to monitor educational trends, assess program impact, and refine its approach for greater effectiveness.

In conclusion, the observed educational imbalance across Kerala districts is not merely a statistical concern—it is a call to action. By identifying and addressing the root causes of these disparities, the Malabar Education Movement aims to build a future where every learner, regardless of geographic or socio-economic background, has an equal opportunity to pursue higher education and achieve their full potential.

Dr. Abdushukoor KM

The Apple International School, Dubai

Reference:

Higher Secondary Result, 2023, University Websites

A Closer Look at Higher Secondary Class Sizes Across Kerala: Patterns, Problems, and Policy Directions

Kerala is widely celebrated for its educational achievements, but not all regions share the same classroom reality. The chart prepared at CEDAR analyzing average class sizes in higher secondary schools across the state's districts reveals a stark variation — ranging from under 35 students to well over 60 per classroom. This article delves into the district-wide disparities, explores the underlying causes, and outlines recommendations for more equitable and efficient educational planning.

UNEVEN DISTRIBUTION: CLASS SIZE RANGES FROM 34 TO 64

The data show considerable variation across Kerala’s 14 districts:

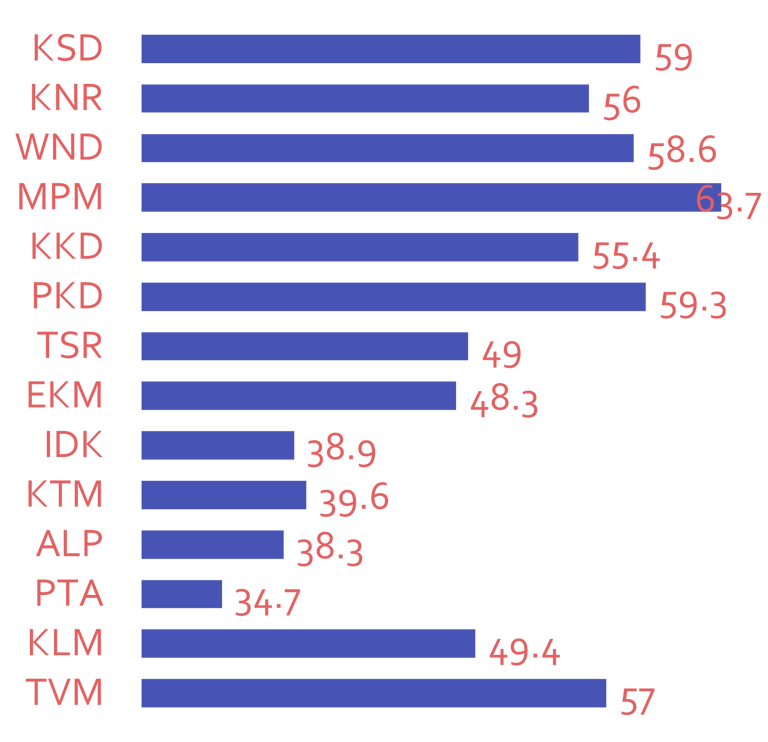

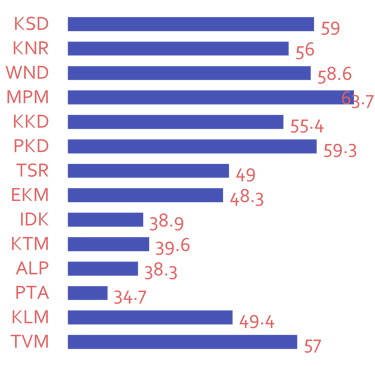

Malappuram stands out with the highest average class size of 63.7 students, far exceeding what is pedagogically ideal.

Other overcrowded districts include Palakkad (59.3) and Kasaragod (59).

On the opposite end, Pathanamthitta records a relatively small class size of 34.7, followed closely by Alappuzha (38.3) and Idukki (38.9).

Such differences suggest a geographical imbalance in both student population distribution and infrastructural provisioning.

KEY REGIONAL PATTERNS

1. Overcrowding in Northern Districts

Districts like Malappuram, Palakkad, Wayanad, and Kasaragod show consistently high average class sizes. Several factors likely contribute:

Insufficient growth in the number of higher secondary schools.

Limited teacher recruitment or classroom expansion despite rising demand.

Higher student populations due to demographic patterns.

The outcome is clear: teaching and learning in these regions may be strained, with teachers facing difficulty in managing large groups and students receiving less individual attention. There has to be a statewide survey on teacher satisfaction to understand the problem better.

2. Smaller Classes in Southern Districts

Pathanamthitta, Idukki, and Alappuzha, show notably lower class sizes, the plausible reasons being high allocation of higher secondary batches, lower birth rates and out-migration that reduces school enrolment. These areas benefit from relatively better teacher-student ratios. However, underutilization of resources may be a concern. Schools with shrinking enrolments may face difficulty justifying staff numbers or maintaining operational efficiency.

3. Urban-Rural Mixed Trends

Urbanized districts like Ernakulam (48.3) and Thiruvananthapuram (57) sit in the mid-range, which might seem counterintuitive. However the presence of private schools and specialized institutions could be absorbing some of the load and public infrastructure in these districts may be more evenly distributed across urban and suburban zones.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY AND PLANNING

1. Targeted Expansion in the North

There is a pressing need to increase the number of higher secondary schools and classrooms in overcrowded districts, particularly Malappuram and Palakkad. Immediate recruitment of teachers and infrastructure investment is essential.

2. Reallocation and Consolidation in Under-Enrolled Areas

In districts like Idukki and Pathanamthitta, resource optimization strategies—such as merging under-enrolled schools or repurposing infrastructure—could help redirect support where it’s most needed.

3. Equity and Quality Must Go Hand in Hand

Kerala’s overall education metrics mask significant intra-state disparities. Ensuring educational equity requires more than literacy drives—it demands granular policy interventions guided by real-world classroom data.

CONCLUSION

The state of class sizes in Kerala’s higher secondary education system is a microcosm of broader demographic, geographic, and policy challenges. As Kerala continues to strive toward educational excellence, addressing regional overcrowding and underutilization must become a planning priority. Data-driven, district-sensitive interventions will ensure that every student—whether in Malappuram or Idukki—has access to a classroom conducive to meaningful learning.

Dr. Muhammed Kutty P V

Director, CEDAR

Reference:

Disparities in School Size Across Kerala: A Data-Driven Snapshot of High Schools

Recent data from Kerala’s Class 10 examination landscape reveals a sharp contrast in school sizes across districts. An analysis of the number of schools — categorized by student population — highlights significant variations in institutional scale and, by extension, resource distribution and educational infrastructure. The number of students passing SSLC exam is considered a proxy for the student population (more than 99% students pass the exam every year for past many decades which justify the proxy).

Two Ends of the Spectrum

The analysis divides schools into two categories:

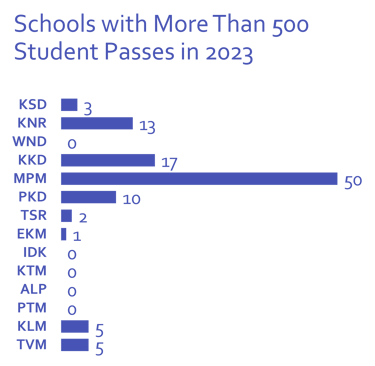

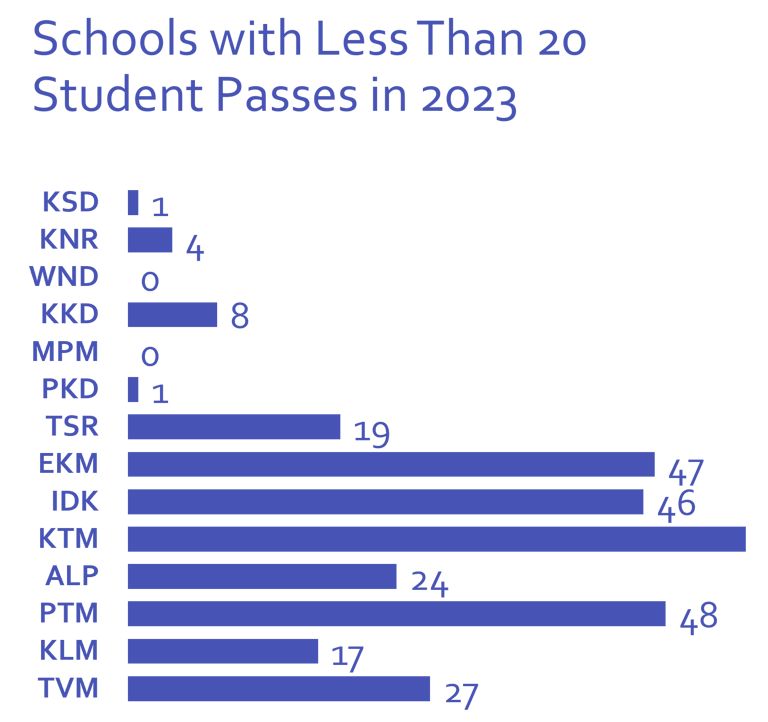

Large Schools (chart 01): More than 500 students moving out every year.

Very Small Schools (chart 02): Fewer than 20 students moving out every year.

All schools included had at least one student pass the Class 10 exam, confirming their operational status. However, the data reveals more than mere academic presence; it underscores systemic structural patterns.

Patterns That Emerge

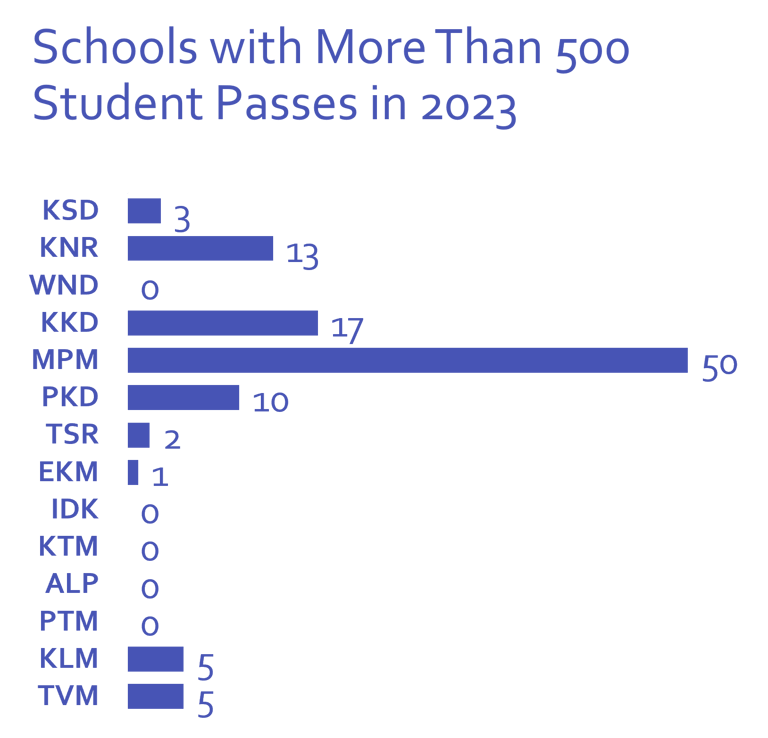

1. Malappuram: Overcrowding at Scale

Malappuram reports 50 schools with over 500 students, and not a single school with fewer than 20 students. While this might be interpreted as a sign of efficient consolidation or population concentration, the reality on the ground tells a different story.

These large institutions are often overcrowded, with stretched resources and limited teacher-student interaction. The result is a trade-off between quantity and quality — where managing numbers becomes the focus, and individualized learning suffers. In classrooms packed well beyond optimal capacity, meaningful engagement, remediation, and experiential learning are often sidelined.

A striking example is PKMHSS Edarikode, where over 7,500 students are enrolled on a campus that spans just 4.25 acres, including all its academic blocks, administrative buildings, and playgrounds. Such density raises serious concerns not only about learning quality but also about student well-being, safety, and access to essential facilities like laboratories, libraries, and open space for recreation.

This model raises deeper systemic concerns:

Are the push toward larger schools compromising foundational learning?

Are infrastructure and staffing keeping pace with enrolment growth?

Are students from outlying or marginalized areas being adequately reached?

Malappuram’s numbers show scale, but not necessarily success. Without robust support systems — more teachers, better infrastructure, and pedagogy suited for large cohorts — school size becomes a liability, not a strength. The district’s case is a reminder that bigger isn’t always better when it comes to education.

2. Small School Clusters and Isolation

In stark contrast, districts like Kottayam (58), Pathanamthitta (48), Idukki (46), and Ernakulam (47) report dozens of schools with fewer than 20 students. These figures raise serious concerns. There could be factors of population decline and migration, but the long-standing issue is also the result of unjustifiably excessive allocations to these districts. Whatever the causes, the prevalence of very small schools often correlates with poor resource utilization, insufficient peer interaction for students, and difficulty in maintaining quality teaching staff.

3. The Dual Reality of Some Districts

Districts like Thiruvananthapuram and Kollam show a bifurcated structure — they have both large schools and many very small ones. This points to unequal development within the district — where some areas may have high social capital to gain excessive resources from the government while some other regions remain underserved owing to low social capital. Thrissur offers another unique imbalance: only 2 large schools versus 19 very small ones. These cases reflects the presence of strong regional disparities within these districts.

Implications for Policy and Planning

The findings invite immediate attention from education planners:

School Consolidation: Where feasible, merging very small schools into larger, better-resourced institutions may improve student outcomes and staff allocation.

Transport and Access Planning: In geographically challenging districts, improving transport to nearby larger schools can balance size without harming access.

Resource Reallocation: Infrastructure investments should prioritize high-need districts such as Malappuram to reduce the over-centralization of educational services into selected schools which will drive further social divide.

Demographic Analysis: Further correlation with population density, migration trends, and rural-urban splits is essential for targeted policy action.

Conclusion

Kerala’s education system is globally admired for its literacy and outcomes — but this data reveals fault lines in institutional size distribution that may undercut long-term educational equity. A data-backed approach to planning and reform is not just advisable — it’s imperative.

Dr. Muhammed Kutty P V

Director, CEDAR

Reference:

https://sametham.kite.kerala.gov.in/

SSLC Result 2023

CHART 02

CHART 01

SUPPORT OUR EFFORTS

Your support matters.

Donations to MEM help us advance our mission to promote Equity, Equality, and Quality in education. Our research is already making a measurable impact in Kerala—and with your support, we can do even more.

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Malabar Education Movement

Account # 9210200 51515180

IFSC: UTIB0003700

Axis Bank, Chevayur, Calicut, Kerala, India

CONTACT

Office Address

Aksharaveed

Near Kannamparamba Gate

Kothi Approach Road

Calicut - 03

Phone: +91-7902907827

info@memeducation.org